The Modern Changeup: The Best New Pitch In Baseball

The changeup is the most historically misunderstood baseball pitch.

Despite slight differences in grip, most other pitches are thrown in the same way across pitchers.

A slider has defined spin, a mixture of bullet-spin, forward and side spin that creates a visible red dot.

A curveball has defined spin, topspin moving in a 12-6 or 1-7 orientation with as true a spin axis as possible.

The grip might differ slightly, but the way spin is applied, which may be the biggest factor in throwing a breaking pitch, is largely the same.

But, what about the changeup?

The changeup, for no good reason, is confused. The change up is supposed to be…

…slower.

This is likely the only thing changeup throwers all agree on. But, how much slower? Six miles per hour? Eight? 10? 12? And, straight?

Straight changeups are sooooo old-school.

Pull the string! But what about James Shields’ heavily-sinking changeup? Sink is good, right? He strikes out right-handers regularly with that thing. And, how about some arm-side run? That’s always a plus. Which version is best? What type should a young pitcher aim to develop?

And, what grip will get him there? Circle change? Vulcan change? “Fosh” changeup? Hook ‘em horns grip? Three-finger? Palm ball? Or, if all else fails, we can just say screw it and just throw a splitter; that’ll work as a poor-man’s changeup.

There’s too many questions, too much confusion with the changeup. Let’s clear it all up.

Characteristics of The Modern Changeup

First, let’s get it straight: a changeup does have a defined set of characteristics, and not all grips are created equal. Most people just aren’t on board with this yet. The best changeups feature the following:

- Excellent arm speed that appears identical to the fastball

- Speed reduction of 8-12% (miles per hour value varies depending on fastball velocity)

- A combination of arm-side movement, known as “run,” and sinking movement.

James Shields is one of the best examples. Watch the short video below to see what I believe is the modern changeup:

Let’s consider the following:

Straight or Moving?

If all other parameters are equal, a pitch that has movement is harder to hit than a pitch that is straight.

Though a straight change perhaps looks exactly like a straight fastball (thus making it very deceptive), pure deception isn’t the end goal. The end goal, rather, is a mis-hit or swing and miss. When the hitter’s brain must deal with both speed change and movement away from the initial trajectory of the pitch, the likelihood of weak contact increases.

Pitchers want to create as many variables as possible to prevent the hitter from getting barrel to ball.

How Slow?

The answer depends on the other big half of the equation: movement.

From my years pitching professionally, my experience has been that the more movement a changeup has, the harder it can be thrown. Essentially, it’s no different than a slider or cutter Think about Noah Syndergaard’s extra-hard “slider,” and how hard it is to hit.

When a pitch is thrown harder, it flies longer along the same trajectory as a fastball.

When these harder breaking pitches finally do move off the fastball’s path, it makes them appear to break more suddenly, sharper, which in turn makes them more difficult to square up. The more speed we remove, the more the pitch must deviate from a fastball’s initial trajectory, thus making it look less like a fastball out of the hand.

The basement of speed change is about 8%. For a pitcher who throws 90mph, this is about 7mph off, or 83mph. But, a -8% changeup must have tremendous movement to be effective.

For all other changeups, as movement decreases, speed change must proportionally increase. If a changeup is dead-straight, being closer to a 12% reduction is ideal (79mph off a 90mph fastball).

There are many times when we pitchers get away with a changeup that was thrown a little too hard because late movement caused it to fade off his barrel at the last moment.

How Hard?

This is basic, but needs to be addressed in any good changeup article.

A changeup needs to be thrown with as much intensity as possible. The “harder” a changeup is thrown, the more it matches fastball arm speed, and initially fools the hitter into thinking that 90mph arm speed = 90mph output. We need 90mph arm speed with a 79-83mph output.

What allows this to be possible is the grip and hand action, both of which play equal parts in reducing the velocity output.

What About Cutting Changeups?

Kyle Hendricks purposefully cuts his changeup sometimes. But, this is just another iteration of his changeup, a different way for a him to manipulate hitters.

Though this works quite well for him, it’s not the standard version for most pitchers, for one main reason: pitchers need a pitch that breaks away from opposite-handed hitters.

If we cut our changeup, how does it vary from a slider?

Not much, is the answer.

As a right-handed pitcher myself, I threw more changeups to lefties, because I didn’t want my curveball breaking down and in, into their happy zone.

For a veteran pitcher who throws a curveball, sinker, sinking changeup, mixing in an occasional cutting changeup will definitely confuse a hitter. But, that’s much more of a thing Big Leaguers do to stay effective, and much less the rule we teach an amateur or minor leaguer who needs consistency more than anything.

Throwing The Modern Changeup

If we compromise on a goal of 10% speed reduction, which will be ideal for the majority of pitchers, we need to understand how we obtain that reduction.

We get about 5% from the grip itself, and 5% from the hand action.

Breaking pitches are slower than fastballs not because they are thrown with less intensity. Rather, that arm speed and velocity is lost into the baseball by spinning it.

This is the same for the changeup.

When force is applied to the center of the baseball, the baseball will come out hard, because all of the available arm speed is going into propelling the ball forward and applying backspin. Aside from slowing the arm or hand down, or not “finishing” the pitch, there’s no reliable way to reduce the speed of a changeup when force is applied through the center.

This is why we need a defined hand action that converts speed into spin.

The grip will only account for a 5% speed reduction when force is applied to the center of the baseball. That equals 4.5mph off a 90mph – much too hard to be effective.

The hand action provides the second 4.5mph, and that action is the same as a sinker, and somewhat opposite of a slider: pronating the hand on the inside of the ball just before release.

By pronating the hand onto the inside of the ball just before release (think pouring out a can of soda), we accomplish two things:

- We reduce speed because less force is applied to the center of the ball; we are converting speed into spin just like a breaking pitch

- We tilt the axis of rotation of the ball to a diagonal axis, which will result in angled downward movement – a mix of both arm-side lateral movement (run) and sink.

And with that, we have given the changeup a reliable set of characteristics just like any other pitch. When thrown the above way, we will reliably achieve a 10% (plus or minus) speed reduction that can easily be repeated at any intensity. We also create a reliable movement pattern for the hand, creating relatively equal parts sink and lateral movement.

A few of my high school pitchers threw to the Rapsodo device and turned in spin-efficiencies of 90% or better, indicating a very “clean” diagonal spin axis on their changeups, confirming that what I believed was happening.

Depending on the pitcher and his unique way of executing the pitch, the output will vary slightly. I’ve taught this exact style of changeup to hundreds of pitchers, and 70% will obtain a 10% speed reduction with equal parts lateral and sinking movement. 15% will throw get the same speed reduction with predominantly lateral movement, and another 15% will get the same speed reduction, but only sinking movement.

Provided the speed reduction is there, anomalies in movement are okay, and to be expected – no two pitchers are alike. I have one collegiate pitcher who throws the pitch with a 15% reduction, no decrease in arm speed, and heavy, fork-ball like sink with no lateral movement whatsoever.

The ball comes out in a unique way, with a tumbling spin rather than an angled axis. But, the output is fine for him – it’s different, but still exceptionally effective. He reminds me of Brad Lidge, who threw a slider that appeared to have mostly downward movement. His slider wasn’t the archetypal slider, but it still had deadly effect as shown by his season of 41 saves without a single blown opportunity.

Even with consistency in teach methods, there will be an inconsistency in output. But, most pitchers will develop a changeup that consistently fits the aforementioned mold.

Can All Changeup Grips Accomplish This?

In short, no.

There are a few conditions that result in more reliable hand action and spin application, which are made difficult or impossible by certain grips.

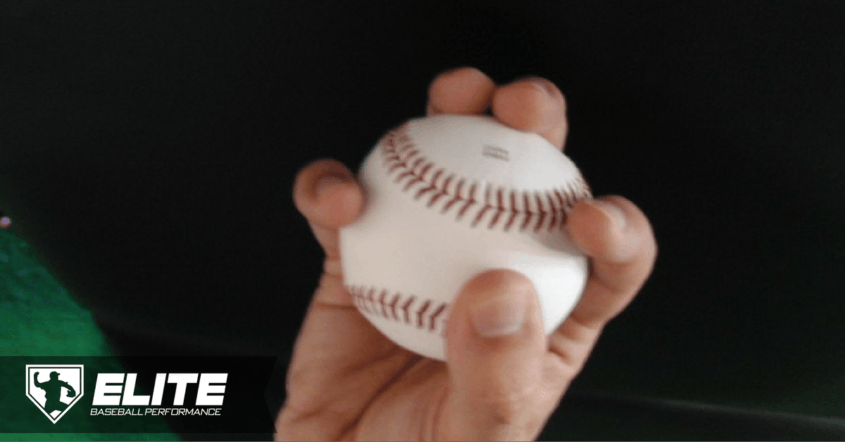

Condition 1: Pressure must be at the junction of the palm and fingers, not on the fingertips.

We maximize lateral spin application by forcing the ball to roll up the fingers before finally releasing off the fingertip. Changeups that start and leave from the fingertips do not gather as much spin, and often fly too straight or “flat.”

Condition 2: The ball must be held stable with as little pressure as possible.

We need to think of “paintbrushing” the hand over the changeup.

But, we need to do this at a 100% intensity, which is difficult. So, we need a combination of the hand being as relaxed as possible while still being held securely. To do this, the thumb must be on the bottom.

Condition 3: Overall hand tension must be as low as possible.

A relaxed hand applies spin more fluidly and evenly, and allows the pitch to more closely resemble a fastball at release. A tense hand also tends to force the changeup into the ground, resulting in spiked changeups that are often the signature of beginners. Forcing the fingers down the sides of the baseball are one of a few culprits that cause undue hand tension.

Condition 4: To accomplish the above, the thumb must be on the bottom of the baseball.

If the thumb cradles the ball from the bottom, the rest of the hand can be almost completely relaxed. If the thumb is not beneath the ball, as in the “circle change” grip, the fingertips will tense up to prevent the ball from simply falling out of the hand. Tension and fingertip pressure will result in the pitcher hooking the pitch into the ground more often.

As a side note, my students rarely bounce changeups while they learn them, because the grip I teach provides a relaxed hand. This is not to say they miss up the in zone; rather, they are able to control the ball in the strike zone most of the time, with the same frequency as their fastball, with fewer egregious misses. The changeup spiked five feet in front of the plate, typical of beginners, is extremely rare in my baseball academy.

Teaching and Throwing the Modern Changeup

This is the first article in a 3-part series on throwing the modern changeup. In part two of this changeup article series, I’ll cover a step-by-step method of teaching and throwing the modern changeup.

In my years as a baseball academy owner and professional pitcher, I’ve taught this pitch with equally great effect to 11-year olds and 25-year old pros. I use a simple step-by-step approach to teaching the pitch the cornerstone of which is watching and giving constant feedback on ball spin. After that, it’s up to the pitcher to put in the time and dedication honing the pitch and learning how to pitch with it.

And, in part three, we’ll discuss the difference in how you pitch with the modern changeup. Righty-on-righty changeups? You bet. Gloveside changeups for called strikes? Not so much. Learning how to maximize the effect of the pitch, and minimize its weaknesses is what takes a pitcher to the next level.

In the meantime, subscribe to my Podcast, titled Dear Baseball Gods and find me on Instagram @coachdanblewett.

Dan Blewett

Latest posts by Dan Blewett (see all)

- What Causes A Mental Meltdown in Baseball? - September 3, 2019

- Two Common Curveball Mistakes Pitchers Should Avoid - July 30, 2019

- Is Heavy Lifting Good For Pitchers? - July 2, 2019

Hey, thanks for the article! It was extremely helpful. Several years before Kendrick started throwing his cut change I had came across the pitch in the Minor League Scouting Notebook. The Mets had a prospect in their system with a solid repertoire but he was having trouble adding an off speed pitch. After a conventional changeup and a splitter didn’t pan out a coach was teaching him how to throw a “cut change”. I’ve read hundreds of scouting reports on pitchers and I had never heard of that pitch. I’ve seen five different sources call one particular pitch five different things, so I figured a “cut change” was some grizzled old coach’s slang for a circle changeup. It was interesting to find out that it was an entirely different pitch.

I have a question for you after reading your article. There are tons of contradictions and conflicting details in scouting reports. A circle change and a straight change are two different pitches, right?? Just about everyone understands that a southpaw throws a circle change to a RH batter so it will sink and tail away from the plate. I’ve lost count of how many I’ve read a report that says a pitcher throws a straight change and that he uses the pitch for the same effect. “This LHP throws a straight change, he turns it over and it sinks away from RH batters.” What’s up with this?! Like I said, I’ve came across it often so it couldn’t be a typo. How can you get the same movement/action using two different grips?

Another quick question, then I’ll let you go. Same scenario but different pitch. I’ve only encountered this a few times and Matt Clement was one pitcher I recall reading about that could run his sinker away from RH batters if he kept it down in the zone. It sounds like a cutter to me but thats not a pitch that is associated with sinking. A sinking two seam fastball does that, except it’s usually moving inside on a RH batter, not away. It gets confusing. Maybe you have an explanation. Maybe this was unique to Clement. I know he had great stuff and his pitches had tons of movement but he constantly struggled with command his entire career. And, unfortunately, it ended too early.