The Other Type of Shoulder Instability: Batter’s Shoulder

Several baseball injuries center around the inherent instability that the shoulder, or glenohumeral joint, provides.

The classic description of the golf ball (the humerus) sitting on the golf tee (the glenoid) is really a great description of how unstable the shoulder really is.

As described often on previous posts, throwing a baseball really isn’t good for you. This is evidenced by having over 7000 degrees of rotational motion in one’s shoulder when throwing.

This violent movement over the course of a season or career can begin to develop stress in the anterior compartment of the shoulder.

Whether this causes an injury as severe as a SLAP (superior labrum anterior to posterior) tear over time is up for debate, but it’s clear that this type of instability is the most common form in overhead throwers, such as baseball players.

When we discuss shoulder instability, we often think of this certain type. Typically, the symptoms include anterior shoulder pain, perhaps from an acute dislocation, subluxation, or a general degeneration of the anterior capsule over the course of thousands of throws.

Introduction: Posterior Instability in Baseball

However, in baseball players, another type of shoulder instability is unique. This phenomenon is referred to as “batter’s shoulder.”

The injury, similar to anterior instability in pitchers, occurs mostly in hitters in their front shoulder from repetitive posterior capsule stresses incurred from swinging a bat. This stress is highlighted more so by instances of swinging and missing as well as swinging at outside pitches, where the front shoulder is subject to a greater moment of adduction.

This type of posterior instability is also seen in another type of unique population: football interior lineman, whose arms are always in a position of shoulder flexion with combined adduction holding onto the opponent’s shoulder pads. Through the continued line of force produced axially through their arms, posterior shoulder problems can arise.

For the purpose of this topic, we will focus on the baseball population. This type of injury is not nearly as common as anterior shoulder instability from throwing. Not often do we see player’s heading to the injured list for “batter’s shoulder” or “posterior shoulder instability,” yet it’s important from a clinician or rehab professional’s perspective to understand the inherent risks that our athletes face.

Phases of Batting

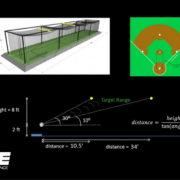

Just like throwing, hitting has phases, too. Shaffer and colleagues have stated that the traditional baseball swing goes through four distinct phases. These include the wind up, pre-swing, swing, and follow-through.

While throwing a baseball may be the fastest movement in sports, hitting a baseball can generate high shoulder movement speeds too. These same authors have stated that rotational velocity at the shoulder is 937 degrees per second–still a violent, powerful movement.

How Does Batter’s Shoulder Work?

Once we take this great amount of force produced at the shoulder and combine that with the mass of a baseball bat, albeit a small weight (typically around 2 pounds), we can begin to see how the repetitive amount of swings can impart stress onto the shoulder.

For another way to look at the effect of hitting, think about it like this. At the higher levels of competition, hitters swing the bat hundreds of times in a 5-day span, between game swings as well as the batting practice, etc., we can compare that to the amount of throws that pitchers throw over the same 5-day stretch.

In addition, it should be recognized that pitchers throw with a 5 oz. ball and hitters must use at least a 31 oz. bat in most cases. However, while a hitter uses an object that is 6x heavier than a baseball, the rotational velocity at the shoulder during pitching is approximately 7x that of swinging a bat.

It’s also important to note that anterior shoulder instability often occurs in the throwing arm of a baseball player. Posterior instability usually occurs in the front, non-throwing shoulder, unless the player hits on the opposite side of the plate, i.e., a right-handed thrower who hits from the left side.

This type of usage and repetitive force on the front shoulder that is not used for throwing will be critical when discussing the treatment options.

The 500-N Elephant in the Batter’s Box

As discussed earlier, swinging and missing on an outside pitch is often considered the main mechanism in a baseball setting for developing posterior instability. Kang and colleagues have determined that this type of circumstance can generate as much as 500 Newtons of “dynamic posterior pulling force” during a swing.

While 500 N may not sound like anything significant, this amount of force represents greater than about 110 pounds of force being pulled posteriorly for your shoulder to absorb. Imagine this amount of force produced over the course of a season or even a career.

While the weight of the bat, in addition to the rotational velocity and force at the posterior shoulder is important, the angle of the shoulder plays a great role in this equation.

As the shoulder is in increased horizontal abduction from a position of approximately 90 degrees of shoulder flexion, the shoulder is going to be in more a congruent, stable position with the glenoid, which is angled at about 30 degrees away from the body.

Once the shoulder moves into greater horizontal adduction (arm crossing the body) of approximately 105 degrees, as it would be the case in swinging for an outside pitch, it’s clear that the posterior shoulder would sustain more impact in this position.

The American Sports Medicine Institute group (ASMI) emphasized this arm angle with injury, stating that it may increase shear forces across the shoulder joint. This evidence truly underscores the stress that the shoulder can incur.

Swinging and missing can also develop more damage to the posterior capsule of the shoulder due to the shoulder muscle’s inability to contract as it normally would with making contact with the baseball.

So You Have This “Batter’s Shoulder,” Huh?

The typical presentation for batter’s shoulder often involves a feeling of instability, especially after reaching for an outside pitch or simply swinging and missing.

After these moments of instability, it’s also common for athletes to feel discomfort or pain with provocative positions, such as forward shoulder flexion, adduction across the body, and internal rotation, as they all function to stress the posterior shoulder capsule.

Often, during a clinical examination, the jerk and Kim tests are very good to stress the shoulder. Tannenbaum and his colleagues have described both these special tests and Kim et. al determined that the combination of both these tests have a 97% sensitivity for posteroinferior labral lesion.

The normal course of action for this type of instability from a labral deficit often begins with conservative therapy. Kang described that interventions will focus on rotator cuff strengthening, scapular stabilizing, and improving generalized mobility.

In the event the patient does not improve with conservative treatment, surgery is indicated to arthroscopically repair the posterior labrum.

From here, the patient will undergo a period of protected motion, motion recovery, strengthening, plyometric training, and sport-specific training. Kang reports that patients can often progress to taking swings from live pitches at 6 months after surgery following an appropriate return to hitting program.

Let’s Step Out of the Batter’s Box

Kang reports that the average return to sport after surgery is approximately 6.5 months with very often, excellent outcomes, without any common significant complications.

Altogether, batter’s shoulder is very rare in the realm of musculoskeletal conditions, yet a common mechanism in a baseball population.

As a health care provider, it’s important to recognize posterior shoulder pathology and the mechanism in which it can occur. This can often occur by completing a thorough subjective history and being able to replicate the instability-provoking movements.

This is an outstanding article. I have often thought about the violence of reaching and missing for an outside pitch. Also, the fact of the repetitive motion of swinging a bat and use of the shoulders. I coached multiple sports for over twenty years and can’t wait to share this. I am definitely saving this article!

Thank you,

Brian E. Nosek

I got this web site from my buddy who informed me

about this website and now this time I am browsing this web page and reading

very informative articles here.

My question is, how do you prevent this from happening again? My son has rehabbed, PT’d, works out and it still happens specifically when he’s early and has to “reach” for low and away pitches. It’s to the point now that he just wants to quit playing altogether (he’s in college).